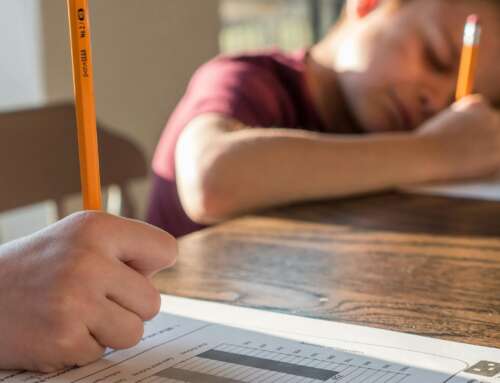

The middle years of school are defined as being from 8-14 years of age. These were often described as a latent or quiet phase of development.

We now understand this is not the case — the middle years are a foundational period for development. But there is not enough support in the education system to help young people during this period — which includes the often stressful transition from primary to secondary school.

The importance of the middle years

Much of our new understanding on the importance of the middle years comes from studies looking at the effects of puberty, such as the Childhood to Adolescence Transition Study (CATS). This has been following 1,200 Melbourne students from when they were in Year 3. In 2020, members of the group are aged 16-17.

Most of our knowledge of puberty has focused on a period that begins at around 10-11 years of age with the production of oestrogen and testosterone. This results in the development of secondary sexual characteristics (breasts, facial hair) and the ability to reproduce.

Before this period, is a process that begins at around 6-8 years of age with a rise in adrenal hormones. These hormones lead to the development of armpit hair and pubic hair, as well as acne.

Apart from infancy, the biological changes of puberty bring the greatest shifts in brain development. These pubertal changes drive a different engagement with the social world.

During the middle years, which coincide with puberty, peer relationships become increasingly important. In a recent study, we found two-thirds of students between the ages of 8 and 14 reported being bullied frequently in the past four weeks. And 35% reported frequent bullying in multiple forms, such as physical and verbal attacks.

It is now increasingly recognised bullying peaks during these middle years — rates are typically lower in early primary school. For boys, bullying declines with age, but for girls it persists into secondary school.

How children’s health affects education

There is a close connection between health and education during the middle years, particularly in the transition to secondary school.

In a typical classroom in mid-primary school, around five students have emotional problems and five have behavioural problems. These students will begin secondary school a year behind their peers in numeracy skills.

This is independent of the presence of developmental vulnerabilities children may have when they start school. These include having problems that impact physical health and/or language and communication skills.

Governments have invested heavily in preschool education and preparing children for school entry, such as increasing funding for more children to attend kindergarten. They also invest in identification and support of younger children with particular developmental vulnerabilities. But the middle years haven’t seen the same level of commitment.

In 2015, the Victorian Auditor General tabled a report into school transitions (early childhood to prep, prep to primary and primary to secondary). It noted the education department …

has developed a comprehensive and well-researched framework to support early-years transitions. This has led to a greater uniformity of approach and contributed to improved early-years transition outcomes. However, it does not provide the same levels of support and guidance to schools to transition students from primary to secondary school.

Similarly, there is still a lack of evidence-based, system-wide strategies that adequately respond to the educational, social and emotional needs of children in the transition to secondary school. This is despite evidence a stressful transition to secondary school may have long-term negative outcomes, such as school disengagement and poor academic performance.

The middle years have also been neglected when it comes to health. There have been major investments in service delivery systems for students in the early years and older adolescents (such as Headspace). In contrast, little attention has been given to the middle years. Yet one half of all adult mental health problems emerge by age 14 with symptoms often appearing in the preceding years.

Remote learning could have made it worse

Remote learning and physical distancing during COVID- 19 may have an unequal effect on students’ mental health and learning during the middle years.

Remote learning could cause greater disengagement and loss of learning for students who have recently transitioned to secondary school. With the disruption, many students may not have established strong routines and relationships with peers and teachers.

Students who fall behind during this period may find it difficult to catch up without proper support.

During the middle years, there is a shift in the relationship between parents and children — as children start to orient away from parents, towards their peer group. These changes can be seen as an opportunity to reestablish parent-child relationships, especially in the COVID-19 climate.

Research shows when parents are interested in their child’s learning, involved in an age appropriate way and have good communication with their child, it helps the child’s development, reduces risky behaviours and leads to fewer mental health problems.

Parents’ involvement in their child’s learning also leads to better academic performance and stronger school engagement.

The rise in remote learning and move to COVID-normal offers a chance for parents to become more actively involved with their child’s learning.

Beyond the family home, schools are the most important context for development. School teachers can successfully identify students that are likely to encounter issues in Year 7. Connection and familiarity between teachers and students can improve engagement with school.

Teachers also have an important role in providing a positive social environment for peer relationships and skill development.

Although the middle years are a time when students are at risk of school disengagement and health problems, these years are also a time of opportunity. Environmental effects, such as the school and peer environment, are particularly strong and intervention may have the greatest impact.

All young people must be supported during this phase of life. And governments must provide targeted programs to support those most at risk.

This should be aimed at strengthening social and emotional learning, improving the primary to secondary school transition, and enabling more effective links between education and health services.

This article was written with input from masters student Helen Ramsay.![]()

Lisa Mundy, Senior research fellow, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

Leave A Comment