Taren Sanders, Australian Catholic University; Chris Lonsdale, Australian Catholic University; David Lubans, University of Newcastle; Michael Noetel, Australian Catholic University, and Philip D. Parker, Australian Catholic University

Australian children are among the least active in the world. In a recent study, Aussie kids ranked 140th out of 146 countries for physical activity.

And in 2018, a physical activity “report card” gave Australian children a D-minus for overall physical activity levels. The grade was based on only 18% of young people meeting the physical activity guidelines — 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity each day.

We developed and tested a program that trains teachers and schools to enhance the physical activity of their students long-term. And it costs just a fraction of some government policies that have shown limited results.

Government policies not meeting their goals

State policies typically require primary schools to provide students with at least two hours of planned physical activity each week. This doesn’t just have to be physical education classes and can include sport, energiser breaks and more active lessons. Still, many schools fail to meet these recommendations.

Australian children’s competency in fundamental movements are alarmingly low. For example, governments recommend children master an overarm throw by year 4 because it’s a gateway to many sports. Yet, evidence suggests 75% of year 6 girls have still failed to master this skill.

To address these problems, schools and governments have spent a lot of money on attempting to increase physical activity in kids.

For example, the New South Wales government recently spent $207 million over four years to subsidise children who enrol in sport outside of school. The Active Kids policy gives each eligible child a $100 voucher for the cost of sports registration, membership expenses and fees for physical activities such as swimming, dance lessons and athletics.

These vouchers do appear to be effective for children who use them. But an evaluation showed a substantial number of parents in socially disadvantaged groups didn’t know about the program, or just weren’t engaging with it. This is arguably the group who needs them most.

Plus, the vouchers cover only a few hours of sport per week. Children spend the rest of their time with their parents and teachers. And we know 85% of Australian adults don’t meet the required physical activity guidelines.

Teachers can be trained to help

Teachers have a lot on their plates, but equipping teachers to promote physical activity can have long-lasting benefits. Teachers can pass on new skills to thousands of students over their career.

The skills teachers can learn don’t have to be complicated. For example:

- well-meaning teachers may spend more than half of their physical education lessons with children being inactive, such as when giving instructions. Lessons could jump into active games that require minimal instruction

- classroom teachers can add five-minute “energiser breaks” of physical activity between lessons

- schools could make recess and lunch more active with a few hundred dollars of equipment or setting up games with the equipment they already have.

Many teachers already use some of these strategies, but promoting them more widely is a cost-effective way of getting children moving without compromising other school priorities.

How we know it works

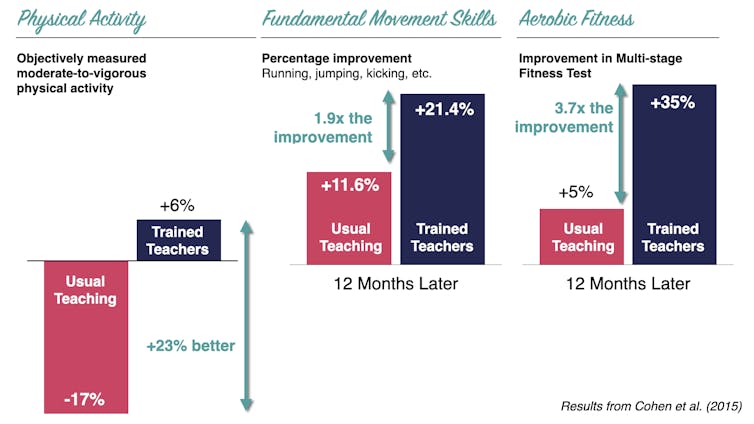

We compared the fitness of students that received a specific intervention in four primary schools, with students in four primary schools that carried on as usual. In total, 25 classes including 460 children participated in the study (199 children in the intervention group and 261 in control group).

The interventions involved several phases, including training teachers in strategies such as the ones above, giving kids awards for progress and enhancing school policies themselves to encourage fitness. We provided some basic equipment to schools like balls, markers and sashes.

In the schools that received the interventions, students’ fitness, physical activity, and fundamental movement skills improved significantly more than in the schools that carried on as usual. That is, children spent about 13 more minutes per day doing moderate-to-vigorous activity (huffing and puffing) and, as a result, were better at running, throwing, jumping and catching.

To make things cheaper and easier to scale, we then moved most of the teacher professional learning online, and used some digital technologies to give teachers extra feedback. Teachers received some face-to-face support, with specialist physical education teachers giving each teacher an hour of mentoring.

Our revised program, iPLAY, doubled the usual fitness gains children got over a two-year period. It worked twice as well in children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, and it only cost $16.50 per student per year.

Being so affordable, our small team was able to deliver the training to 189 Australian schools.

Our calculations show we could improve the health of Australia’s 2 million primary school children for just one-third of the the cost of the four-year Active Kids program in NSW.

And, by supporting teachers, we are building capacity in schools for the long-term.![]()

Taren Sanders, Research Fellow, Institute for Positive Psychology and Education, Australian Catholic University; Chris Lonsdale, Professor, Institute for Positive Psychology & Education, Australian Catholic University; David Lubans, Professor, University of Newcastle; Michael Noetel, Senior Lecturer in Psychology, Australian Catholic University, and Philip D. Parker, Professor and Deputy Director, Institute for Positive Psychology and Education, Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

Leave A Comment