Encounter Youth

As a parent of two young children, I have become increasingly aware of how many questions parents have, as well as the countless conflicting opinions on how to raise a child well. My children are not teenagers yet, so I have not yet had to deal with the delicate topic of alcohol and other drugs with them. Through my work in the field, however, I have come across countless parents trying to find out how to best tackle issues such as underage drinking and other drug use.

These parents often end up with more questions than answers, or feel helpless to do anything to encourage positive behaviour in their young person. I want to make it clear that each parent is absolutely the expert on their young person. However, what do we actually know from the research when it comes to parenting, alcohol, and other drugs?

- Young people learn from what they see

Parents often underestimate how much influence they have on their young person’s decisions. Young people’s perceptions of social norms are shaped by their parents, and the behaviours that parents model can impact their young person. For example, parental modelling of healthy behaviours (such as moderating or eliminating alcohol consumption) has been shown to reduce the amount that young people drink, both now, and later in life1.

- Parenting style can have a big impact

“‘Effective parenting’ incorporates a warm and supportive parent–child relationship that

includes setting clear and consistent boundaries and is accepting of the need for psychological autonomy”2. For example, having open lines of parent-child communication, where a young person is free to explore their views and opinions, helps them feel like their opinion is being heard. A parent is then aware of their young person’s thoughts and concerns, can provide feedback in an open, non-judgemental way and can provide reasons to support the rules that they have in place. This style of parenting, termed ‘authoritative parenting’ has been shown to reduce underage drinking and other drug use in young people, as well as increase various other wellbeing measures3.

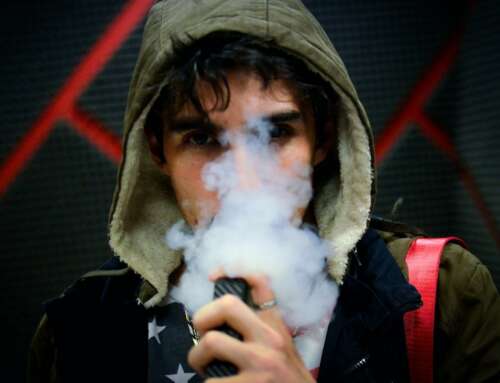

- Even ‘just a sip’ may influence drinking habits

There are many contexts in which a parent may allow their child to drink underage. It may be a sip of the parent’s wine, offering a beer over dinner, or sending them to a party with a limited amount of alcohol. From the research, it is clear that the more a young person is permitted to drink by their parents, the more likely they are to engage with underage drinking and drink at risky levels later in life. But what about those little sips? Research in the USA showed that even small sips can contribute to a young person’s later decisions about drinking alcohol. Australian research is currently underway to better understand the effect of parents or others giving sips of alcohol to young people. Given the current evidence, the Australian alcohol guidelines state that for people under the age of 18, no alcohol is the safest option.

Our encouragement to parents is to think about the role of alcohol in their home, what they are modelling to their children, and to provide clear, consistent boundaries about what is expected. The behaviours that parents model, as well as their years of parenting investment, significantly influence the choices young people make, even in the teenage years. As we encourage parents in our Party Safe Education seminars: these years are a time to trust your teen and your parenting!

– Andrew Scholefield

More information about Encounter Youth and their Party Safe Education seminars is available from their website www.encounteryouth.com.au.

References

- Ryan, S., Jorm, A., and Lubman, D., 2010, “Parenting factors associated with reduced adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of longitudinal studies”, 44 (9), 774-783

- Ward, B., and Snow, P., 2008, “The role of families in preventing alcohol-related harm among young people”, Prevention Research Quarterly, 5

- Steinberg, L., 2001, “We know some things: parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect”, Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11 (1), 1-19

Leave A Comment