David Armstrong, RMIT University

At a press conference last week, paralympian Dylan Alcott recalled the pain of being a child with a disability.

“I had no friends when I was five,” the Australian of the Year told reporters. “I even got goosebumps saying that.”

He said one of the positives about the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) was that it had helped today’s young kids develop almost twice as many friendships. But how?

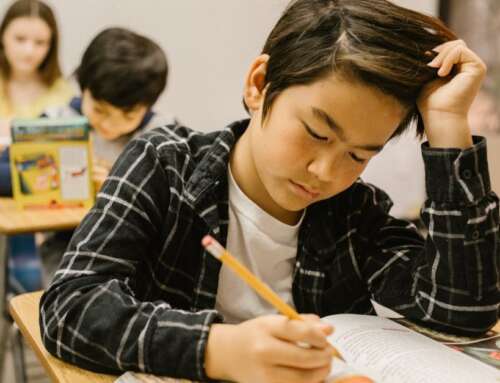

School is a crucial place to think about friendships for kids with disabilities because, as research confirms, it’s a space where all kids learn to make and maintain friendships. Some studies imply that schooling plays an even more important social role for students with a disability than for typically developing kids – with non-disabled students modelling appropriate behaviours.

Friendships matter for kids with a disability – without them, kids will not flourish in school, feel lonely and be isolated. So how can we help some of our most vulnerable students make and maintain them?

Disability and social isolation

Alcott’s comments echo what experts know about disability and social connection. A study of English adults published last year shows: “Compared to the general population, people with disability have fewer friends, less social support and are more socially isolated”.

According to several studies, the quality of friendships for many young people with disabilities is reduced, compared to young people without a disability. (Friendship quality is measured against criteria including status as peers, variety of activities enjoyed together and these activities being spontaneous rather than prearranged or programmed group events.) This lowers quality of life.

Negative social attitudes toward disability compound this social disadvantage in schools and in our communities.

Although small progress has been made in Australia toward addressing these ingrained attitudes in the school system, they still persist as shown at the Disability Royal Commission public hearing on education in 2020.

At the 2020 hearing, students with disabilities reported losing access to friendships as well as learning if they are excluded from school and sitting at home. Once excluded, students have even fewer chances for social interactions and friendships.

Friendship is about access

My own research highlights how students with a disability are seriously over-represented among kids asked to leave settings or suspended, usually on account of their behaviour – and what might address this problem.

Lacklustre or tokenistic application of policies on educational inclusion is a more subtle problem. Well-meaning policies applied without considering a child’s social needs mean a child might be physically present in the classroom of a regular school but without classroom friendships or experiencing the wider social life of the school.

Advocates point out genuine inclusion is about access to friendships and social opportunities children with and without disabilities might not have considered or encountered otherwise.

And decades of international research finds strong friendships mean young people are less likely to develop aggressive behaviours or a mental health condition. This finding is particularly important for children and young people with a disability who may be at increased risk of severe psychological distress.

Making moments, calling out issues

The finding that NDIS participation boosts friendships shows that with sufficient support and adequate funding, social success is entirely achievable.

Parents, teachers, school leaders and concerned members of communities can help too. Parents play a key role in kids’ friendship development, facilitating opportunities for children with and without disabilities to bond in groups or one-on-one.

Pexels, CC BY

Adults can call out segregation, discrimination and cultures of low expectations lurking in school systems.

Kids with disabilities can be enabled to participate in whatever aspects of the wider school social life interest them. Non-disabled students may have a negative bias towards kids with a disability and that can prevent relationships. Resources such as the ABC’s You Can’t Ask That can be used in schools to tackle stereotyping.

Students with disabilities often face bullying. Effective school-wide anti-bullying programs are essential for helping them navigate positive relationships. The governments’s Bullying No Way program is a good example.

Friendships can have unique challenges for kids with autism, but providing explicit teaching about social rules among the neurotypical can help. Research-supported specialist programs exist. Nurture groups can give kids focussed support to gain and maintain relationships.

The benefits of friendships and strong social inclusion for children and young people with a disability are compelling. As a society we should do all we can to prevent some of the most vulnerable in our communities from falling into a lonely and isolated life.

David Armstrong, Senior Lecturer in Special and Inclusive Education, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Leave A Comment